The walrus’s most distinctive feature is its tusks. They can grow to up to an impressive meter in length, and both males and females have tusks. Walruses were once very abundant in the Svalbard Archipelago, but were nearly hunted to extinction during the Middle Ages for their ivory. Walrus ivory was very popular during the early Middle Ages, and a famous example of objects made out of walrus ivory are the Lewis Chessmen. The growing trade in walrus products in medieval Europe led to overexploitation of walrus populations, and the population on Svalbard was brought to the brink of extinction. In 1952, walruses on Svalbard became protected. The population is slowly increasing but walruses remain on the Norwegian Red List.

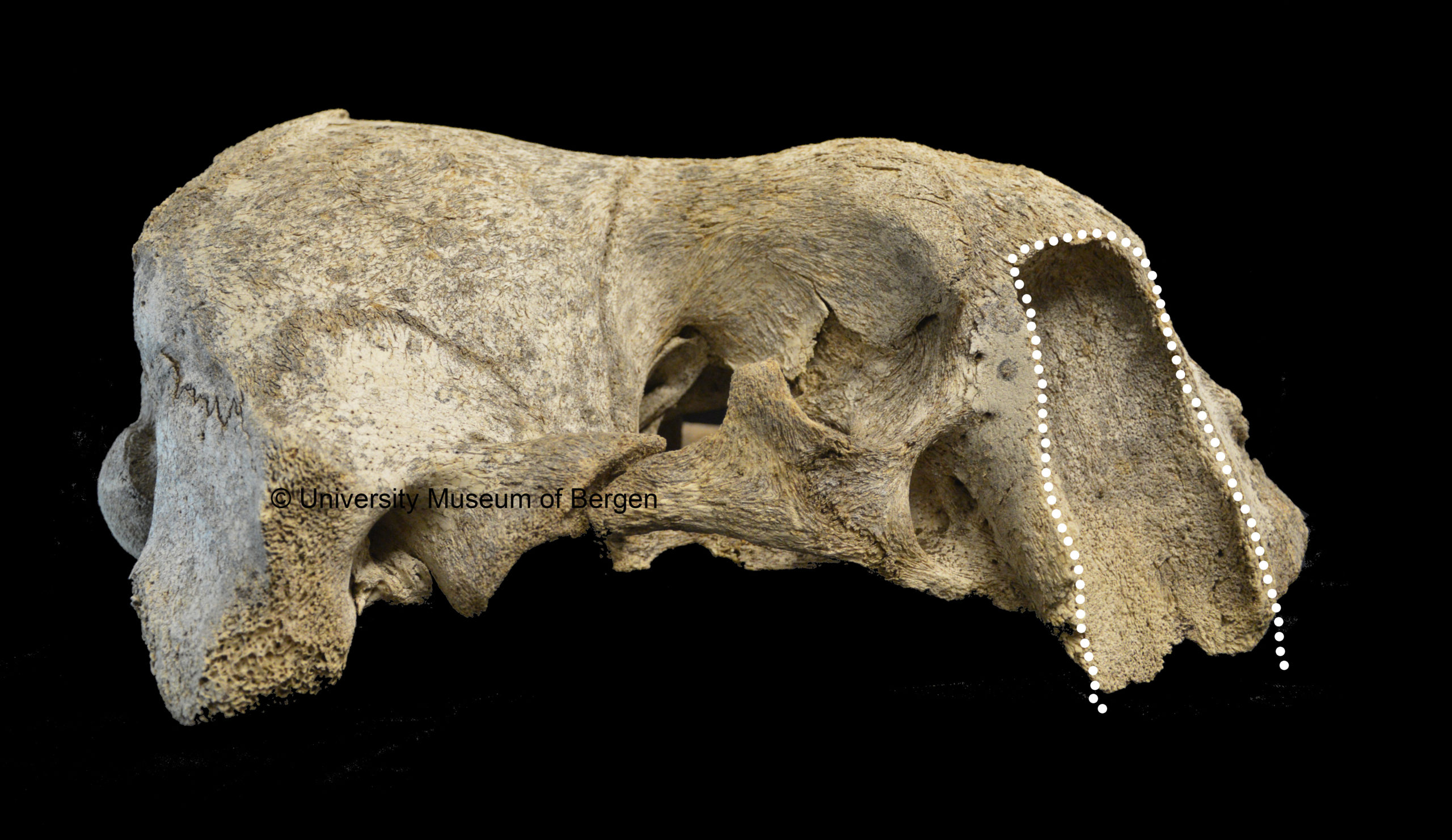

The Osteological collection of the Bergen University Museum contains many archaeological walrus skulls, such as the one in the picture above, that still bear the signs of this overexploitation. According to archaeologist James Barrett, walruses were slaughtered in a consistent way where the frontal part of the skull, the rostrum, was chopped off in order to remove the tusks. The marks left behind by the chopping can still be seen in many of the skulls (indicated by the dotted line).

More on how the North Atlantic walrus ivory trade was linked to the boom and bust of the Norse settlements in Greenland: https://titan.uio.no/naturvitenskap-livsvitenskap-english/2020/boom-and-bust-economy-greenland-norse-walrus-ivory-trade